It’s a new year and the Core SBTF Team is busy developing its roadmap for. We have recently expanded the Core Team with experienced volunteers who have done phenomenal work on previous SBTF deployments. We are also updating our Ning platform, blog, Facebook page, etc. For example, we recently added a Coordinators Page and Deployments Page on our blog.

Since launching in October the SBTF has engaged in no fewer than 18 (!) deployments. Of these, a total of 9 were “Official Deployments” while 9 were “Side Deployments.” Official Deployments are those for which the activating organization meets all our “Activation Criteria.” For example, the activating organization must clearly demonstrate & explain:

- A direct need for the live map

- How they will use the data collected

- The capacity to respond on the ground

We had actually not anticipated the idea of “Side Deployments” when we first set up the SBTF. But we soon found ourselves asked to support a number of live mapping initiatives that did not directly meet our criteria. But we had the time and indeed considerable interest from SBTF volunteers to get engaged regardless, particularly if we were not in the middle of an Official Deployment. Side Deployments have given new volunteers an ideal opportunity to develop their skills and master the various workflows of the SBTF. So they have become really key to our work.

Of the 18 deployments, 2 were simulations with UN partners; 2 were elections related; 6 were in response to “natural” disasters such as floods and earthquakes; 6 were conflict related; 1 was related to public health and 1 to activism. October was the first time we had 2 deployments in one month; while December saw no fewer than 4 individual deployments. The longest deployment was the Libya Crisis Map which took about 4 weeks. The shortest deployments ranged from 2-3 days in duration.

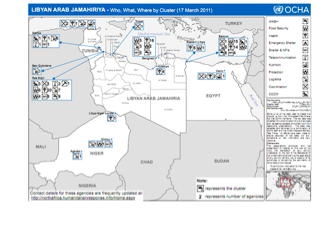

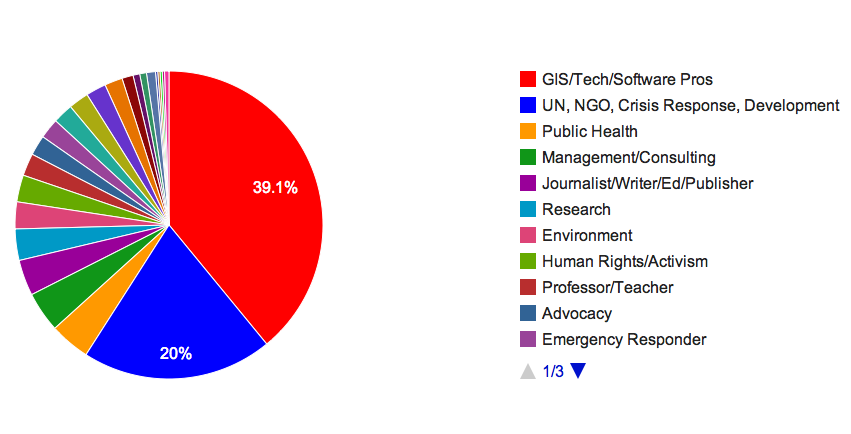

In terms of the groups activating the SBTF, the UN (OCHA, UNHCR, WHO) activated the Task Force 5 times and twice for simulation exercises; Civil society group 6 times; Amnesty International (USA) once; ABC Australia once; Al-Jazeera once; and local disaster management agencies twice. In terms of specific SBTF Teams activated for these deployments, the Media Monitoring Team, Geo-Location Team and Reports Team are most often activated. This makes sense since these teams represent core information management processes. The newest member to the SBTF is the Satellite Imagery Team, which was activated twice in the Fall of. The Translation Team and SMS Team have yet to see action in a live deployment.

While reviewing this list of SBTF deployments, I was also struck by another realization. Of the 18 deployments, a total of 14 involved the use of the Ushahidi platform. The other 4 leveraged other platforms like OpenStreetMap (OSM) and Tomnod. For each of the 14 deployments that used Ushahidi, the SBTF was not involved in the decision to use the Ushahidi platform. Each time SBTF volunteers used an Ushahidi platform following an activation, it was the activating organization that either had already set up an Ushahidi platform or directly requested the use of an Ushahidi platform. Indeed, of those 14 SBTF deployments, no fewer than 11 already had an Ushahidi platform set up even before the SBTF was contacted.

The 4 SBTF activations that did not use Ushahidi all took place within the past few months. This is perhaps an indication that our efforts to diversify are finally starting to pay off. When we launched the network in October we immediately reached out to multiple partners including OSM & Sahana and repeatedly invited them to train SBTF volunteers so they would have additional “surge capacity” available to them. While Sahana has yet to RSVP, our colleagues at OSM did provide 1 introductory training about a year after our first invitation.

Since then, SBTF volunteers have also been trained in using the Tomnod platform for micro-tasking satellite imagery analysis. In addition, two companies recently approached us offering their information management tools for free along with pro bono training. We look forward to evaluating these tools and integrating them into our workflows if appropriate. Incidentally, other tools that we couldn’t live without for the work we do include our dedicated Ning platform, Google Groups & Apps and Skype.

Our modular team-based approach and corresponding workflows are not tied to a particular piece of software but rather reflect core aspects of knowledge management and information processing. Indeed, each of our Teams represent key information management processes. This explains why the workflows for the Media Monitoring Team, Geo-Location Team, Analysis Team, Satellite Team, Verification Team, Task Team and Humanitarian Liaison Team are basically independent of the Ushahidi software. The only team that requires experience in using the Ushahidi platform is the Reports Team. But even then, the Reports Team can be trained in adding content to other platforms, like OSM.

This setup is deliberate since otherwise we would considerably constrain ourselves and make it impossible to scale and adjust to different needs. In sum, we are pragmatists and platform agnostic. The reason why the original 50+ volunteers of the SBTF were Ushahidi experts was because they were the ones behind the ground-breaking crisis maps of Haiti, Chile, Pakistan and Russia, which all used the Ushahidi platform. Indeed, they were the pioneers and the energy behind the creation of the SBTF that same year.

Another interesting observation is that we recently started to get involved in deployments that do not map events or incidents, but rather infrastructure (e.g., health facilities in Libya and shelters in Syria). Indeed, we just had our first health-related deployment and hope to get involved in projects related to environmental issues in the near future as well.

Standby Human Resources

SBTF volunteers have consistently demonstrated they are a reliable, hard working and creative bunch. On little notice, they are willing to put in hours of their free time, all the while holding a job / writing a PhD / entertaining three toddlers. Their encouragement and interaction with similar volunteers comes through a computer screen - emails, skype emoticons and the occasional call. Most SBTF skype chat rooms are full of positive comments (we once did a wordle of a deployment skypechat, and “(rock)” featured pretty prominently).

All that said, sometimes nerves can fray and conflicts flare up. As a growing network, we increasingly need to put systems in place to ensure we can maintain harmonious relations, especially at times of stress. This is why we have put together a formal SBTF Complaints Protocol, which you can view here.

In order to manage complaints, we have also set up a Human Resources Team. The HR team is responsible for providing support on issues relating to human resources to the entire SBTF, in particular:

Two experienced SBTF volunteers (Leesa Astredo and Christina Kraich-Rogers) will be the Coordinators of this team and will be responsible for:

A standbytaskforce.com needs standby human resources. Together with the psychological support recently added to the SBTF, we hope this new HR Team will help us all keep working in happy, productive and welcoming environment.